BMW shows off its self-riding bike

German firm working on a robot bike – but you’ll still need to ride it

WE CAN sort of see the point of a self-driving car. Most four-wheeled transport is merely mundane meat moving of course, and if you could just sit in the back and get pissed, read a book or sleep on your way home from work, who wouldn’t?

But bikes are a bit different. Not only would you struggle to have a sleep on the back of an autonomous S1000RR, there’d not be much point would there? Much of the bike experience is about enjoying the ride – and from the feedback we already see about stuff like traction control and wheelie control, most riders want to keep control of their machines.

So why are all the bike firms working on smart, autonomous, self-riding ‘robot bikes’? We went to Marseille in the south of France with BMW to find out the hot take from Munich. The German firm has a test track there in the suburb of Miramas, which lets them ride prototype bikes all year round, when Bavaria is under feet of snow. There’s a giant banked outer ring, a huge oval circuit, enduro track, handling track and a small race circuit too (you can see it on Google Maps here).

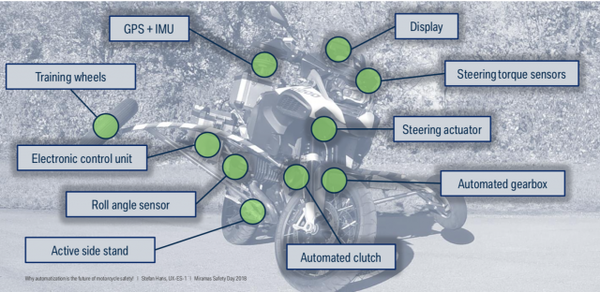

We saw a few cool things in our day there – not least a new electric super-naked machine which looked incredible. But this self-riding R1200 GS was a big hit. We’ll get into the ‘why’ in a moment, but first, how does it work? Well, it’s actually remarkably simple – the modded GS only has a steering actuator motor, clutch, throttle and gear inputs, plus an automatic sidestand. The computer doesn’t get anything else to help it – no special gyros spinning to keep it upright, or extending steering heads, as on the Honda self-riding bike shown last year. When you think about it, that sort of makes sense – after all that’s all a human rider uses to ride – albeit with the small added bonus of being able to move their bodyweight about.

The GS’ panniers and topbox are stuffed with computers, GPS units and sensors, which do the job of keeping the bike upright and moving (or putting the stand down when it stops), and also keeping an eye on the world round about, so it can avoid obstacles and prepare its route.

The test rider rode the bike into the test track, and jumped off. Then, the bike set off itself – which is pretty spooky at first. It wasn’t hanging about either – the big old GS rorted off, and did a series of figure-of-eights, curves and turns, all within the quite tight paddock area we were in. When it came to a stop, it casually stuck out a stand on the right-hand side, flopped itself over onto the stand, then sat there, ticking over like a robotic-overlord boss. Smart.

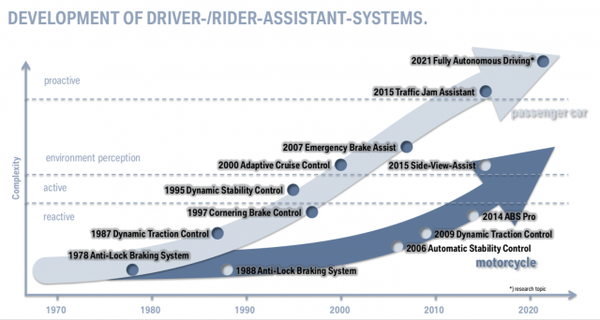

The computing power on this GS is being used to develop a self-riding algorithm which will give BMW the ability to build a bike that *could* ride itself. But it won’t, generally. What it’s planned to do is help build a variety of possible extended ‘safety nets’ for the future. At the moment, the current safety nets of ABS and traction control are able to take over in very tightly-defined ways to prevent an isolated ‘bad thing’ happening. They can stop the front wheel locking on a patch of ice, or a highside out of a wet roundabout, say, and that’s prevented a lot of accidents. But it is limited in terms of the accidents it can prevent (and compared with the tech safety advances in cars, we're not doing well enough – see chart below).

ABS can’t help with a car turning right in front of you, or pulling out of a blind junction into your lane. It certainly can’t help when you get target-fixated in a tight bend and drift wide into the front of a bus, even though there was enough lean and grip potential in the situation to avoid crashing.

But in future, if your bike has an overall ‘intelligence’, which is plugged into the sensors and networked information sources that will be here soon, it will be able to step in and prevent a much wider range of accidents. So, with data from a self-driving car which is coming out of a blind turn ahead of you, your bike will ‘know’ that a possible impact is ahead, and warn you to take action. If you miss that warning, it might elevate things rapidly, and ultimately take over control itself, braking and swerving to avoid the other vehicle.

Plus, a very advanced set of safety algorithms may be able to step in when riders make errors of their own – like panic-braking mid-bend or not leaning over enough to get round a tight corner. If your bike knows exactly what’s around it (a bus coming the other way), where it is (a tightening left-hander), and what it’s doing (going a bit fast, only leaning half as far as it could, and drifting out into the bus’s path), it can predict what might happen (you hitting the bus). Then it could take over – leaning the bike farther, reducing engine torque, applying some rear brake). An intriguing possibility.

Why is BMW (and other firms) investigating this area with such urgency? Well, as they told us in Marseille, self-driving cars and smart highways are coming – soon, and whether we like it or not. At the moment, there’s little regard paid to the needs of motorcycling, and how it will fit into the infrastructure of the future.

If the firms don’t provide an answer to ‘how will bikes become safer and work with other autonomous vehicles’, no-one else will. And all of us two-wheeled addicts might have little choice, but to sit in the back of a self-driving car, supping on a beer, and thinking of better times…