Should MotoGP adopt ‘Superlicence’ requirement to stop Darryn Binder like moves?

Darryn Binder's controversial Moto3-to-MotoGP move has raised the idea of introducing a Superlicence system to stop such leaps... but is it worth it?

The news that Darryn Binder will make his MotoGP debut next season directly from Moto3 may not have come as a surprise given the prior weeks of speculation hinting towards it, but that doesn’t mean it hasn’t generated fairly significant debate up and down the paddock.

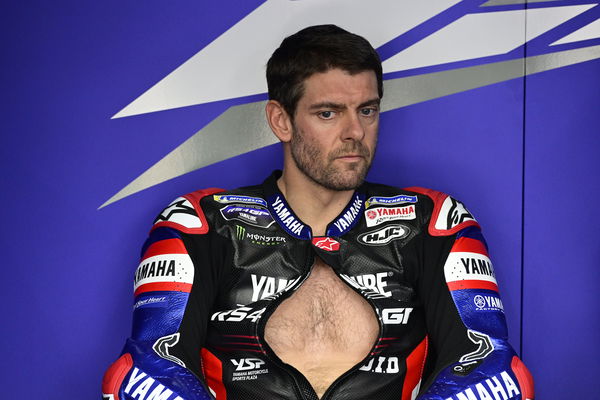

If you’re not up to speed, here is a catch up for you: Binder, younger brother of KTM Factory racer Brad, will compete with RNF Yamaha Racing (née Petronas SRT) in MotoGP next season in a move that will see him step from Moto3 into the premier class.

No matter which angle you look at it, it’s an interesting signing - not just for what it represents but for what it could potentially mean for youngsters coming through the ranks in future.

Competing in his seventh season of Moto3, Binder isn’t lacking match day experience per se, but at the same time he isn’t exactly decorated with success. During that time he has achieved a single win and a total of six podiums from 115 GP starts.

It means he will have 117 races under his belt by the time his MotoGP debut in Qatar rolls around next year. This actually makes him more experienced than some other riders who will be racing alongside him on the grid in 2022, such as fellow rookies Raul Fernandez (60) and Fabio di Giannantonio (107).

Remarkably, he has in fact started MORE GP events than 2020 MotoGP World Champion Joan Mir, who will also have 107 starts chalked up by the start of 2022.

However, these riders have all plied their trade in Moto2 before getting their MotoGP shots, which is what makes Binder’s move so unconventional and under the spotlight.

First and foremost, any criticism of such a switch should A) not be levelled at Binder, because who knows if he’d get another MotoGP shot if he turned it down and B) should perhaps be held until he actually gets to throw a leg over the M1.

After all, he could turn out to be a revelation… and it’s not as though Razlan Razali and Johan Stigefelt don’t have form where this is concerned. Eyebrows were raised when it plucked Fabio Quartararo from Moto2’s midfield for 2019… two years later he becomes MotoGP World Champion.

Of course, Binder already races for Razali’s Petronas Sprinta Racing team, while Stigefelt is a dab hand at spotting talent beyond what happens on track. It wouldn’t risk promoting Binder if it hadn’t seen something in the data to suggest it could have a pliable, eager to learn youngster on its hands to mould into a superstar, much like Quartararo.

Even so, Quartararo - despite middling form on middling bikes in a more spec-driven series - at least had some record-breaking junior results to indicate his true potential.

By contrast, Binder has spent a long time in Moto3 for a fairly modest return in terms of results and it is this fact that forthcoming rivals are more wary about.

How would a MotoGP 'Superlicence' work?

Aleix Espargaro - a rider never shy in airing his opinion despite his own rather ignominious record of ranking ninth on the all-time list of MotoGP starts (195) yet hasn’t yet topped the podium - is certainly baffled by the situation, calling it ‘the strangest move’ he has ever witnessed.

In his response he raised the idea of MotoGP adopting a so-called ‘Superlicence’, as used in F1.

The licence in an F1 context was originally devised to stop drivers boasting more money than experience (ie. skill) joining the grid, though this has become less of an issue over the last 20 years as more stable finances deter teams from dipping into the ‘wealth-over-talent-pool’.

However, the Superlicence was overhauled again in the wake of Max Verstappen getting his F1 shot aged only 17 and with only a single season of car racing behind him. As part of the changes, it was determined that licence credits would be given depending on where they finish in feeder championships with a higher value to more relevant series (such as F2 and IndyCar) over others (such as F3 and WEC). A driver must then attain a certain number of these credits to qualify for the Superlicence they need to race in F1.

It has served its purpose for the most part, though it’s worth pointing out that under this system possible F1 Champion-in-waiting Verstappen, together with other former champions like Fernando Alonso, Jenson Button and Kimi Raikkonen, wouldn’t have got their F1 debuts when they did had this been in place back then.

Point is, Espargaro reckons this is a format that could work for MotoGP. Quite what form it would take is open to debate.

It probably wouldn’t be popular to insist riders who compete in Moto3 wouldn’t qualify for a Superlicence without racing in Moto2 first. After all, Pedro Acosta was being celebrated for a possible direct step to MotoGP in the wake of his stunning 2021 Moto3 campaign, yet it should be pointed out that this is his first season on the GP scene, so in theory is probably less qualified than Binder in experience alone despite their disparity in terms of headline success.

Depending on how far it went, Fernandez might also find his MotoGP spot called into question by the letter of the regulations, despite Moto2 form that has put no-one in doubt that he is deserving of his Tech 3 KTM shot.

Moreover, even the two most recent MotoGP World Champions Quartararo and Mir might have found their debuts frowned upon under the context of such a format had it been in place.

Then again, at a time when the FIM is being forced to introduce minimum age limits amid concerns over accelerating rider development programmes, a Moto3 to MotoGP move perhaps doesn't quite send out the right message of matured talent over raw talent.

Why MotoGP's sheer quality is Binder's problem

The problem for Binder is perhaps more to do with the current era of MotoGP, more specifically its quality and closeness right now.

Indeed, there have been numerous examples in the past of teams deciding seats with their accountant rather than the data over the years.

Well-heeled Christophe Ponsson got a surprise MotoGP debut with Avintia Ducati at Misano in 2018 and was so criticised by other riders for being off the pace, the embarrassed team dropped him from a planned second outing at Aragon.

The CRT era of MotoGP raised a question about the standard of racers as an influx of new privateer teams meant some leanings towards the wealthier rider, but the scrapping of that sub-category and the shift by manufacturers to bring their satellite concerns under factory-guidance means almost every bike on the grid is capable of winning, meaning the riders need to be too.

With this in mind, Binder faces an uphill task with sizeable attention and pressure trained on him… but his challenge is not an insurmountable one.

As Espargaro himself points out, Binder is large and lanky, which does have its impact in Moto3 where being featherweight in slipstream-dependent pack racing sometimes has a greater effect on the results than sheer talent does.

Moreover, as manufacturers have found before with proteges they have signed from junior days, Moto2 doesn’t always quite deliver the brief of allowing talent to shine. Indeed, despite a control-spec engine and largely identical chassis, there is a wide disparity in the budget of the teams, a significant detail that could make-or-break a career if a rider finds themselves lost mid-pack in a competitive series.

Look at Xavi Simeon, Tito Rabat and Thomas Luthi, riders with heaps of experience who flopped in MotoGP because they were too tuned into Moto2-style racing to adapt.

MotoGP’s wider variety makes it clearer if a rider is performing well, whether it’s a comparison to a team-mate or a factory team or other rookies. It won’t hurt to have his brother Brad, not to mention ultra experienced team-mate Andrea Dovizioso no doubt offering their input.

Moreover, there is an argument for MotoGP teams making the most of a developing talent, one it can mould and evolve to its equipment rather than potentially being stuck with a square peg riding style trying to adapt to the round hole of a bike.

Time will tell, but if Binder can at least keep it sunny side up enough and not finish last in every race then it could change the way teams view potential prospects.

If he doesn’t, then don’t expect another Moto3 to MotoGP move for some time… if ever!