A Short History of Single-Sided Swingarms

‘Mono arms’ are a dying breed – here’s why they rose and fell

The recent unveiling of Ducati’s new 2025 Panigale V4 (below), whose most conspicuous update is the loss of its iconic single-sided swingarm, seems to suggest that the era of the single-sided swing arm is coming to an end.

Which, in some respects, is a shame, as the ‘single-sided swinger’, that ‘design work of witchcraft’ where the rear wheel from some angles seemed supported only by magic, has been one of the most striking design features of high-end motorcycles of the last 40 years.

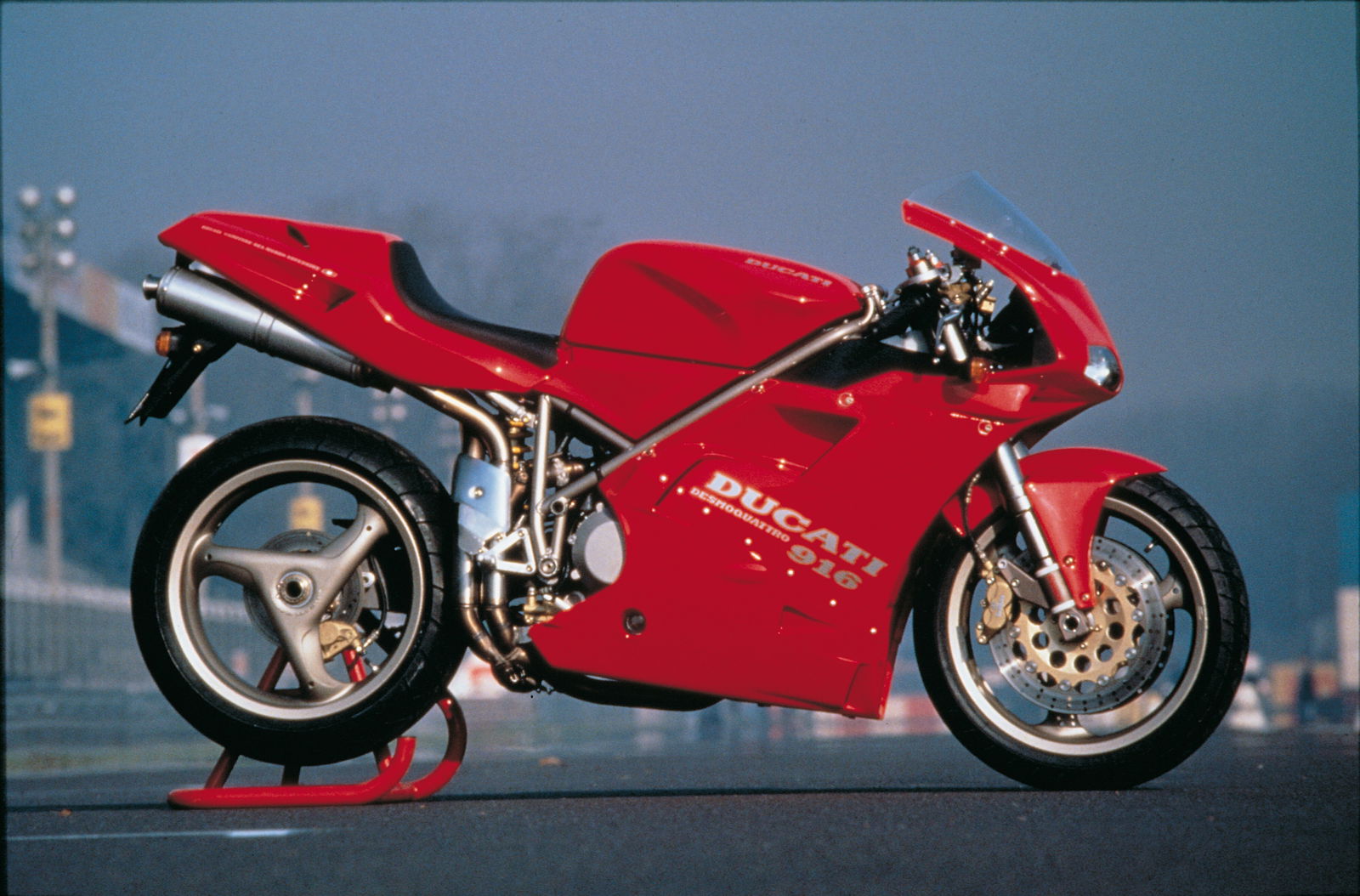

Would the 1987 RC30 have been as memorable – or successful – without its single-sided swing arm and ‘floating’ 18-inch rear wheel? Would the 1994 Ducati 916 have been as significant without its striking single swinger? The same was true of a myriad of others, the NR750, VFR750F, Triumph Speed Triple…the list goes on.

So, what are we talking about, exactly? Where did they come from, what were the advantages and why are they now dying out?

In simple terms, a single-sided swingarm is a style of motorcycle swingarm. The swinging arm is the part of the chassis which allows the rear wheel to move up and down thus enabling rear suspension when that movement is controlled, usually by a system of springs and shock absorbers. A conventional, ‘twin arm’ swinging arm, sometimes called a fork, is double-sided, bracing both sides of the wheel’s axle.

Most early motorcycles had rigid or ‘hardtail’ rear ends with swinging arms starting to become commonplace from the 1930s onwards, usually with twin shock absorbers, one on each side. From the 1980s these were increasingly lightweight but rigid box-section aluminium with single ‘mono’ shock suspension units replacing twin shocks mounted behind the engine.

Early monoshocks were often cantilever type, positioned under the fuel tank and then levered directly by the swing arm. Quickly, more compact systems were adopted whereby linkages multiplied the lever effect enabling smaller suspension units to be positioned directly above the swing arm pivot.

A single-sided swing arm, as its name implies, holds the rear wheel from one side only thus giving the impression from the other that the wheel is unsupported. This has two main advantages: potentially much faster wheel changing, as, like a car, the wheel simply needs to be unbolted from the hub, possibly just via one nut (which is an obvious benefit in long-distance racing such as endurance); and two, its ‘cleaner’ look gives styling advantages. But there are disadvantages, too, which we’ll come back to…

Because of both of those advantages, many people associate the single-sided swing arm most with Honda’s 1987 RC30 production racer which dominated endurance racing for a decade and spawned a popular, more affordable 400cc version, the NC30 and its successor, the 1994 RC45.

Dubbed ‘ProArm’, Honda’s sophisticated, cast aluminium design was the main fruit of a long-term association with the French ELF concern, which raced a series of innovative RS and NS500-powered GP racers through the 1980s and patented the system.

Other production Hondas which also used this system during this period included the 1988 NT650, 1990-on VFR750, 1992 NR750 and even ultra-exotic, Japan-only NSR250R (MC28).

Ducati’s 916 adopted a similar system from 1994 after designer Massimo Tamburini was influenced by the NR750, with updated versions then appearing on the Multistrada V2, 1098 and Panigale.

Triumph has also been using single-sided swing arms since its 1997 T595 Daytona, Moto Guzzi and BMW have their shaft-drive versions, while they also feature on Kawasaki’s H2 supercharged family.

In truth, however, although these are the most conspicuous applications of the single-sided swingarm in recent times, they weren’t the first.

Instead, it mostly dates back to the late 1940s (there are some records of a handful earlier than that), being used on the 1949 German Imme, of which just around 80 were built, then, more popularly, on the 1950 Moto Guzzi Galetto.

After that, the most successful system was the ‘Monolever’ shaft drive version introduced by BMW on its game-changing 1980 R80G/S, which then evolved into the Paralever still used, in updated form, today.

So why the demise of Ducati’s versions now? It all boils down to those ‘disadvantages’ mentioned earlier.

Although great looking and helpful for swift wheel changes, chain-drive single-sided swing arms, due primarily to the immense forces and loads involved, are also inherently expensive to develop and heavy compared to a modern ‘twin-arm’. (With shaft drive it’s different as some sort of arm or housing is unavoidable.)

As a result, if you want a lighter, cheaper-to-produce performance bike, a single-sided swinger has little going for it – hence Ducati’s changes to the Panigale and, previously, Multistrada.

If, however, a bike’s image outweighs that, as perhaps with Triumph’s Speed Triple, Kawa’s H2s and Ducati’s Diavel, or if it’s shaft-driven (BMW/Guzzi) the single-sided swinger can live on.

For now, at least.