1985 Championship double - Freddie Spencer

In 1985, 'Fast' Freddie Spencer did something unique in the motorcycle racing arena - the 250cc and 500cc World Championship double

Valentino Rossi can walk on water. He proved that at Donington Park earlier this year. But could he really summon up the inner strength to take part in two separate world championships and win them both?One former motorcycling deity did just that in the 1980s. Freddie Spencer achieved what many thought was impossible, taking both the 500cc and 250cc titles in the same year - 1985. In doing so he shone briefly like a supernova before fizzling out.

And fizzle out is what many feel he did. Freddie's Herculean effort to lift two titles in one season perhaps led to the premature burn-out of a career that could have been even greater. He had a few comebacks, but Fast Fred was never so scintillating again. In hindsight, did he take on too much?

"Yeah, maybe," says Freddie in his clipped, neat and very polite southern drawl. "Taking those two titles took all the effort I ever had. It took its toll. After that I had neck injuries, back injuries, so if I hadn't taken the double, who knows? But I pulled it off for Honda and the team and I wouldn't trade more world titles for what I did that year. But I couldn't have done it without some great people."

It's worth noting these people who helped Freddie. They are none other than Stuart Shenton, ex Kawasaki and current Suzuki GP team chief to John Hopkins, who helped guide Kevin Schwantz to his 1993 500 title; George Vukmanovich - a tuning legend who's lack of stature was inverse to his skill as a mechanic and more; Jeremy Burgess, the ex Randy Mamola, Wayne Gardner, Eddie Lawson and Mick Doohan spanner-man and chief technician, who's been masterminding Valentino Rossi's pit for the last five years.

And Erv Kanemoto.

Kanemoto met up with Freddie in 1979. Freddie has remarked that this third-generation Japanese-American had an uncanny knack to translate what Spencer was saying the bike did, into changes on the bike itself. It all added up to a helluva team.

By 1985 Frederick Burdette Spencer was already a legend. Aged 10 he held titles in five US states; by 13 he was competing in 100 dirt-track races a year, winning the lion's share and learning the art of drifting the rear and going fast and loose. He turned pro at 16 and soon had Kanemoto by his side. After a year or two on two-stroke TZs, a Kawasaki superbike and even a Ducati 900SS, in 1980, aged 18, he was signed to the Honda factory.

Freddie made a few tentative races in GPs before his debut season in 1982, aboard the light and nimble NS500 triple. Thus began his path to GP greatness. He'd win his first 500cc GP race aged 20 at Spa that year on his way to claiming two race wins and third overall.

The following year he'd take Honda's first 500cc championship, making Spencer the youngest ever winner in the process. Making it all the more special was beating Kenny Roberts in his last ever season. Now, in 1985, he'd try and do what no-one had done since Giacomo Agostini in 1972 when the Italian took the 350 and 500 titles.

Freddie says: "At Assen in June '84 Youichi Oguma, Erv and me started thinking about doing the double. We had some success with the upside-down NSR, but we knew it had to be changed and that gave us hope. One thing we didn't have was a 250. At the time Honda was running an RS250. From there we had the genius of Satoru Horiike who did much of the work, with Oguma-san backing him up with commitment from the factory. Horiike developed that 250 from pretty much zero."

For newly-formed HRC, there wasn't the technical back-up that factories have today, as Spencer says: "They didn't have computer models. They had standard dimensions they felt would work but that was pretty much it."

For Satoru Horiike and the team, the answer to build the 250 was simple.

Horiike-san says: "We looked at things and realised we should simply cut the 500 in half! Half a 500 is a 250! At the time we had experience with 500s but not 250s. This was our first factory 250.

We didn't have long to build the bike. From idea to actual machine it was maybe three months. Then that bike to ready-to-race bike another three months."

Horiike and the team then had to literally pre-empt any potential problems with the machine, as Freddie had to develop and test both bikes. How did they manage it all?

"Because back then I was young!" says Horiike-san. "We were all young! We tested every bike from the Kawasaki and Yamaha 250s but we noticed that development time was not enough so we prepared a basic machine and made many test parts. I clearly remember that as the main chassis designer we had to work out the brakes. The 500 had double discs, but for 250 I thought a single disc was enough. I did the calculations and worked out this was enough to give good braking. But I thought maybe we'd have to prepare some double discs, just in case."

Using this 'be prepared' approach, much time was saved during testing, which had to be done as far from prying eyes as possible.Horiike-san explains: "We prepared many, many parts and took these along with the new 250 machine to Suzuka for a test. Normally we used the standard pit at the front of the circuit, but because Suzuka is so long it has a smaller pit around the back. It's small and no-one could see us."

Here's where the workload shot up for Freddie, as he remembers: "This was really the start of the testing situation you see in GPs now. With so many parts and things to test, every lap had to be 100 per cent. Remember, I'm developing two bikes - the new NSR500 and the new 250 - and I want them both to have similar characteristics but the riding style for both bikes is going to be different. We basically simulated everything during a test. We did back-to-back riding of the 250 and the 500 to replicate a practice session ending and starting and did lots of race mileages. I also tried to ride the 500 then ride the 250 straight after, and only de-brief when I was done with both bikes, just like a practice session on a race weekend. It made things very complicated, but I trained myself to do that. It was an approach that Erv and I spent time in the winter developing."

Adding to the workload were the radial tyres, a relatively new proposition in 1985.

Spencer: "We'd had a radial Michelin rear in '84, but a cross-ply front. Sometimes we'd have something like 200 tyres to test. From '85 we had to develop the bikes and the tyres as well as doing a morning's testing on the 250 and an afternoon on the 500."

It was here in testing that people saw the true genius of Freddie Spencer, maybe more so than on the track during a race weekend.

Horiike-san recalls: "Freddie came and we started to test. Freddie was such a good test rider. He was a natural rider so it was very easy for us to test what was good about the bikes and what was wrong. You had to simply look at the laptime. Then it was clear. If he was going fast, that was good, if slow it was bad. For example, with the front brakes. Freddie complained the large single disc pulled to one side in braking. Lap times were slow, so we changed to two, smaller discs which we had already brought along. From that time, front discs had to be double."

By the first GP Freddie had worked out how to approach a race weekend. The critical thing was not just his overall performance but the information he gave his crew to develop two bikes simultaneously, as well as handling tyre improvements from Michelin.

After the pre-season race at Daytona, things weren't going well on the 500.

"During the first GP at Kyalami that thing chattered so bad my teeth hurt," Freddie grimaces, remembering the pain. "It didn't show up at Daytona earlier as the banking meant we had to run a stiffer construction front. I tried everything to win but Eddie Lawson had me beat. I won the 250 race."

It was imperative for Spencer and the team to find what was causing the chatter.

Spencer: "We had three weeks between South Africa and the GP at Jarama. We had a test at Rijeka, in the former Yugoslavia. We tested real hard; tyres, engine combinations, different crank weights, different steering geometry and strengths to see if a bit of flex would help. Eventually we worked it out, but it was the biggest problem we had with the 500, aside from some small stability issues."

With the 500 effort the main focus - "Honda told us the 500 title was the top priority" - new parts were always trickling in, but with the 250, the bike wasn't in line for constant improvements all season-long.

Freddie recalls: "Sure, the 500 we got new parts for, but the 250 development stopped about a quarter of the way through the season. Guys like Honda's Anton Mang and Yamaha's Carlos Lavado were coming on strong and all that time the Yamaha was being developed further. We were a little down on power towards the end of the season and Anton and Carlos were smaller than me so I struggled in some places. We eventually won seven races on the 250, all hard races. You'd have anything between 20-30 laps to go through and all after a draining 500 race. People like Toni Mang never made mistakes. Every corner was hard-fought for."

Spencer achieved his first 250/500 double win during the season at Mugello where help came from an un-looked for source.

"I'd just completed the 500 race and won after a hard battle with Eddie. It was a hot race. I'd been up on the podium and then rushed back to my motorhome, drunk as much water as I could and then tried to get onto the 250 grid on time. It was tight, but Toni Mang - perhaps the greatest 250 rider ever and on a non-factory RS250 - had not left the form-up grid to give me time to get there and take part. What a man. Remember, this was a GP and despite having taken part in a 500 race, I couldn't give these guys a three or four lap head start. You couldn't take time to get into a rhythm, so when I got off the line 10th or 12th it took until the half way point in the race to catch up with Toni and Carlos Lavado. Braking markers, turn-in positions, lines and apexes would all be a little different to the 500. That's why we did race simulations in testing, as in the race you had to respect the guys who were racing in the class. They weren't going to give it to you."

His second double came at Austria that year and a third double looked likely at Rijeka, until he hit a straw bale with his knee, prompting Lawson's caustic, deadpan but hilarious quote to the TV cameras when asked to comment about the incident: "Yes, it was also possible to miss the bale." At Spa and Le Mans came another four wins. Fourth place at Silverstone would secure the 250 crown, allowing Spencer the luxury of concentrating solely on the 500s, but the British event was almost a disaster race.

Freddie was left with a broken right hand following a practice high-side crash in the 250s but he rode through the pain to win the 500 race ahead of Lawson.

"Those races were the hardest," recalls Spencer. "The wet conditions dictated that we had to be very careful to wrap up the 250 series. I had to finish fourth, which means it's sometimes harder to do that than go for the win. The conditions were so bad, it was hard just to survive the race. Silverstone meant we could wrap up the 500 title at Sweden, where I beat Eddie to lift the title.

"It was a proud moment. More so because out of everybody in racing at the time there were maybe only five people who thought I could really do it, and that was my team."

Twenty years on and there are whispers of Rossi contemplating a 250/MotoGP double for 2006. What are his chances, Freddie?

"It would sure be interesting. I think he could have a realistic shot but there's so many variables. But in Jeremy Burgess he's got a crew-chief who knows what it's like and knows exactly how much effort is involved."

Then Fast Freddie smiles and adds: "Actually, I think if Jeremy's memory serves him well on that one, he'll just tell Valentino to stick to the one class!"

DID YOU KNOW

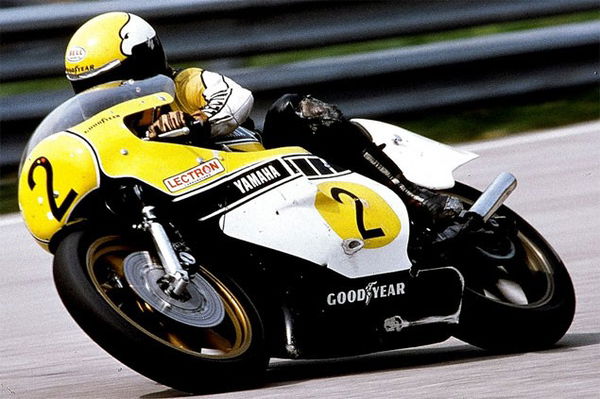

Mention must be made of one other man who could've done the double, seven years earlier. Kenny Roberts made his full-time GP debut in 1978, wanting to win the 500cc championship at his first attempt. He entered the 250cc class too, to get more practice time on unfamiliar tracks. He gave the 250s a miss when he hit tracks he knew, but that didn't stop him winning two races and finishing third in the 250 Championship.

PRESSURES ON A CHAMPION

Every champ has a dark side, a Mr Hyde flipside to the guy standing on the podium, all white-teeth and handshakes before the national anthem. For Freddie, it was the fact that he was so difficult to get on with.

Paddock people at the time remember him as shy, difficult, quiet, taciturn, engaging, reclusive, spoilt and kindly all at the same time. The flipside was that he'd refuse to pose for official team shots or wear leathers with sponsors' branding on them, turn up late for tests and he'd insist on only drinking one brand of fizzy drink which had to be in the garage. He was a two-wheeled pop-star.

But this behaviour simply explains that Freddie had to do what needed to be done to win. And if Freddie worked better without speaking to the press, or having crates of Dr Pepper flown in, who cares? As long as that helped him get to that chequered flag first. Hang everything else.

And that's exactly what HRC did for him. Members of his team from the 1980s still speak respectfully of what he did for them and now, away from the pressure of battling for world titles, this well-spoken, deeply religious man is one of the nicest guys you could hope to bump into.

And bump into him you might if you find yourself Stateside and at the Freddie Spencer High Performance Riding School based at the Las Vegas motor Speedway. In operation since 1997, Freddie currently holds around 30 two- and three-day schools a year aimed at road riders and more advanced schools for racing types. Have a gander at www.fastfreddie.com or call (001) 702 643 1099.

One former motorcycling deity won two championships in the 1980s. Freddie Spencer achieved what many thought was impossible, taking both the 500cc and 250cc titles in the same year - 1985. In doing so he shone briefly like a supernova before fizzling out.

And fizzle out is what many feel he did. Freddie's Herculean effort to lift two titles in one season perhaps led to the premature burn-out of a career that could have been even greater. He had a few comebacks, but Fast Fred was never so scintillating again. In hindsight, did he take on too much?

"Yeah, maybe," says Freddie in his clipped, neat and very polite southern drawl. "Taking those two titles took all the effort I ever had. It took its toll. After that I had neck injuries, back injuries, so if I hadn't taken the double, who knows? But I pulled it off for Honda and the team and I wouldn't trade more world titles for what I did that year. But I couldn't have done it without some great people."

It's worth noting these people who helped Freddie. They are none other than Stuart Shenton, ex Kawasaki and current Suzuki GP team chief to John Hopkins, who helped guide Kevin Schwantz to his 1993 500 title; George Vukmanovich - a tuning legend who's lack of stature was inverse to his skill as a mechanic and more; Jeremy Burgess, the ex Randy Mamola, Wayne Gardner, Eddie Lawson and Mick Doohan spanner-man and chief technician, who's been masterminding Valentino Rossi's pit for the last five years.

And Erv Kanemoto.

Kanemoto met up with Freddie in 1979. Freddie has remarked that this third-generation Japanese-American had an uncanny knack to translate what Spencer was saying the bike did, into changes on the bike itself. It all added up to a helluva team.

By 1985 Frederick Burdette Spencer was already a legend. Aged 10 he held titles in five US states; by 13 he was competing in 100 dirt-track races a year, winning the lion's share and learning the art of drifting the rear and going fast and loose. He turned pro at 16 and soon had Kanemoto by his side. After a year or two on two-stroke TZs, a Kawasaki superbike and even a Ducati 900SS, in 1980, aged 18, he was signed to the Honda factory.

Freddie made a few tentative races in GPs before his debut season in 1982, aboard the light and nimble NS500 triple. Thus began his path to GP greatness. He'd win his first 500cc GP race aged 20 at Spa that year on his way to claiming two race wins and third overall. The following year he'd take Honda's first 500cc championship, making Spencer the youngest ever winner in the process. Making it all the more special was beating Kenny Roberts in his last ever season. Now, in 1985, he'd try and do what no-one had done since Giacomo Agostini in 1972 when the Italian took the 350 and 500 titles.

Freddie says: "At Assen in June '84 Youichi Oguma, Erv and me started thinking about doing the double. We had some success with the upside-down NSR, but we knew it had to be changed and that gave us hope. One thing we didn't have was a 250. At the time Honda was running an RS250. From there we had the genius of Satoru Horiike who did much of the work, with Oguma-san backing him up with commitment from the factory. Horiike developed that 250 from pretty much zero."

DID YOU KNOW

Mention must be made of one other man who could've done the double, seven years earlier. Kenny Roberts made his full-time GP debut in 1978, wanting to win the 500cc championship at his first attempt. He entered the 250cc class too, to get more practice time on unfamiliar tracks. He gave the 250s a miss when he hit tracks he knew, but that didn't stop him winning two races and finishing third in the 250 Championship.

For newly-formed HRC, there wasn't the technical back-up that factories have today, as Spencer says: "They didn't have computer models. They had standard dimensions they felt would work but that was pretty much it."

For Satoru Horiike and the team, the answer to build the 250 was simple.

Horiike-san says: "We looked at things and realised we should simply cut the 500 in half! Half a 500 is a 250! At the time we had experience with 500s but not 250s. This was our first factory 250. We didn't have long to build the bike. From idea to actual machine it was maybe three months. Then that bike to ready-to-race bike another three months."

Horiike and the team then had to literally pre-empt any potential problems with the machine, as Freddie had to develop and test both bikes. How did they manage it all?

"Because back then I was young!" says Horiike-san. "We were all young! We tested every bike from the Kawasaki and Yamaha 250s but we noticed that development time was not enough so we prepared a basic machine and made many test parts. I clearly remember that as the main chassis designer we had to work out the brakes. The 500 had double discs, but for 250 I thought a single disc was enough. I did the calculations and worked out this was enough to give good braking. But I thought maybe we'd have to prepare some double discs, just in case."

Using this 'be prepared' approach, much time was saved during testing, which had to be done as far from prying eyes as possible.

Horiike-san explains: "We prepared many, many parts and took these along with the new 250 machine to Suzuka for a test. Normally we used the standard pit at the front of the circuit, but because Suzuka is so long it has a smaller pit around the back. It's small and no-one could see us."

Here's where the workload shot up for Freddie, as he remembers: "This was really the start of the testing situation you see in GPs now. With so many parts and things to test, every lap had to be 100 per cent. Remember, I'm developing two bikes - the new NSR500 and the new 250 - and I want them both to have similar characteristics but the riding style for both bikes is going to be different. We basically simulated everything during a test. We did back-to-back riding of the 250 and the 500 to replicate a practice session ending and starting and did lots of race mileages. I also tried to ride the 500 then ride the 250 straight after, and only de-brief when I was done with both bikes, just like a practice session on a race weekend. It made things very complicated, but I trained myself to do that. It was an approach that Erv and I spent time in the winter developing."

Adding to the workload were the radial tyres, a relatively new proposition in 1985.

Spencer: "We'd had a radial Michelin rear in '84, but a cross-ply front. Sometimes we'd have something like 200 tyres to test. From '85 we had to develop the bikes and the tyres as well as doing a morning's testing on the 250 and an afternoon on the 500."

It was here in testing that people saw the true genius of Freddie Spencer, maybe more so than on the track during a race weekend.

Horiike-san recalls: "Freddie came and we started to test. Freddie was such a good test rider. He was a natural rider so it was very easy for us to test what was good about the bikes and what was wrong. You had to simply look at the laptime. Then it was clear. If he was going fast, that was good, if slow it was bad. For example, with the front brakes. Freddie complained the large single disc pulled to one side in braking. Lap times were slow, so we changed to two, smaller discs which we had already brought along. From that time, front discs had to be double."

By the first GP Freddie had worked out how to approach a race weekend. The critical thing was not just his overall performance but the information he gave his crew to develop two bikes simultaneously, as well as handling tyre improvements from Michelin.

After the pre-season race at Daytona, things weren't going well on the 500.

"During the first GP at Kyalami that thing chattered so bad my teeth hurt," Freddie grimaces, remembering the pain. "It didn't show up at Daytona earlier as the banking meant we had to run a stiffer construction front. I tried everything to win but Eddie Lawson had me beat. I won the 250 race."

It was imperative for Spencer and the team to find what was causing the chatter.

Spencer: "We had three weeks between South Africa and the GP at Jarama. We had a test at Rijeka, in the former Yugoslavia. We tested real hard; tyres, engine combinations, different crank weights, different steering geometry and strengths to see if a bit of flex would help. Eventually we worked it out, but it was the biggest problem we had with the 500, aside from some small stability issues."

With the 500 effort the main focus - "Honda told us the 500 title was the top priority" - new parts were always trickling in, but with the 250, the bike wasn't in line for constant improvements all season-long.

Freddie recalls: "Sure, the 500 we got new parts for, but the 250 development stopped about a quarter of the way through the season. Guys like Honda's Anton Mang and Yamaha's Carlos Lavado were coming on strong and all that time the Yamaha was being developed further. We were a little down on power towards the end of the season and Anton and Carlos were smaller than me so I struggled in some places. We eventually won seven races on the 250, all hard races. You'd have anything between 20-30 laps to go through and all after a draining 500 race. People like Toni Mang never made mistakes. Every corner was hard-fought for."

Spencer achieved his first 250/500 double win during the season at Mugello where help came from an un-looked for source.

"I'd just completed the 500 race and won after a hard battle with Eddie. It was a hot race. I'd been up on the podium and then rushed back to my motorhome, drunk as much water as I could and then tried to get onto the 250 grid on time. It was tight, but Toni Mang - perhaps the greatest 250 rider ever and on a non-factory RS250 - had not left the form-up grid to give me time to get there and take part. What a man. Remember, this was a GP and despite having taken part in a 500 race, I couldn't give these guys a three or four lap head start. You couldn't take time to get into a rhythm, so when I got off the line 10th or 12th it took until the half way point in the race to catch up with Toni and Carlos Lavado. Braking markers, turn-in positions, lines and apexes would all be a little different to the 500. That's why we did race simulations in testing, as in the race you had to respect the guys who were racing in the class. They weren't going to give it to you."

His second double came at Austria that year and a third double looked likely at Rijeka, until he hit a straw bale with his knee, prompting Lawson's caustic, deadpan but hilarious quote to the TV cameras when asked to comment about the incident: "Yes, it was also possible to miss the bale." At Spa and Le Mans came another four wins. Fourth place at Silverstone would secure the 250 crown, allowing Spencer the luxury of concentrating solely on the 500s, but the British event was almost a disaster race.

Freddie was left with a broken right hand following a practice high-side crash in the 250s but he rode through the pain to win the 500 race ahead of Lawson.

"Those races were the hardest," recalls Spencer. "The wet conditions dictated that we had to be very careful to wrap up the 250 series. I had to finish fourth, which means it's sometimes harder to do that than go for the win. The conditions were so bad, it was hard just to survive the race. Silverstone meant we could wrap up the 500 title at Sweden, where I beat Eddie to lift the title.

"It was a proud moment. More so because out of everybody in racing at the time there were maybe only five people who thought I could really do it, and that was my team."

PRESSURES ON A CHAMPION

Every champ has a dark side, a Mr Hyde flipside to the guy standing on the podium, all white-teeth and handshakes before the national anthem. For Freddie, it was the fact that he was so difficult to get on with.

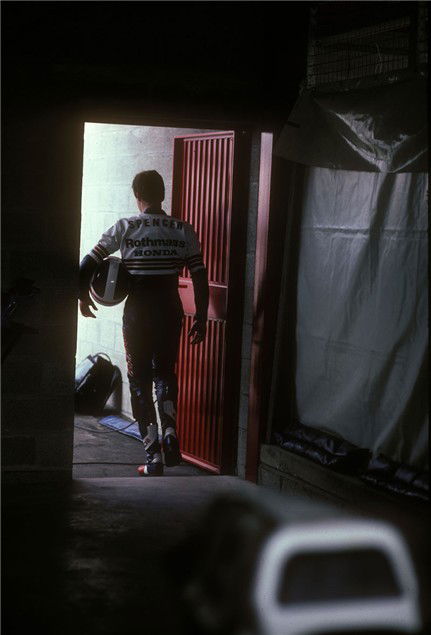

Paddock people at the time remember him as shy, difficult, quiet, taciturn, engaging, reclusive, spoilt and kindly all at the same time. The flipside was that he'd refuse to pose for official team shots or wear leathers with sponsors' branding on them, turn up late for tests and he'd insist on only drinking one brand of fizzy drink which had to be in the garage. He was a two-wheeled pop-star.

But this behaviour simply explains that Freddie had to do what needed to be done to win. And if Freddie worked better without speaking to the press, or having crates of Dr Pepper flown in, who cares? As long as that helped him get to that chequered flag first. Hang everything else.

And that's exactly what HRC did for him. Members of his team from the 1980s still speak respectfully of what he did for them and now, away from the pressure of battling for world titles, this well-spoken, deeply religious man is one of the nicest guys you could hope to bump into.