How the Triumph Bonneville was born and took the world by storm

With the unveiling this week of a new Triumph Bonneville it’s timely to look back at the birth of the original, way back in 1959.

WHILE today, ‘Triumph Bonneville’ is arguably motorcycling’s most famous name, on top of a pile that includes the Harley ElectraGlide, Norton Commando and Honda GoldWing, it’s less well known that the original was intended only as a short-lived special.

Instead of being a mainstream model designed to last decades, the first Triumph Bonneville was simply a special performance version of Triumph’s 650cc Tiger twin built at the request of its US distributor and named in honour of a 1956 land speed record attempt.

In fact, Triumph boss Edward Turner was so wary of the Bonneville project, he reportedly famously said during its development, "This, my boy, will lead us straight into Carey Street” (referring to where the bankruptcy courts were).

Instead, he couldn’t have been more wrong…

The Bonneville’s ‘back story’ is 1950s America’s fascination with motorised independence, bigger, more powerful machines and, ultimately, speed records.

Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats had become the world centre of vehicle speed records and in 1953 witnessed the German NSU factory raise the official FIM motorcycle speed record to 180mph with a supercharged 500cc streamliner.

However, spurred by national rivalry so close to the end of WW2, down the road at Pete Dallio’s Triumph dealership in Dallas, a bunch of poker-playing pals, on hearing the news, were less than impressed. Legend has it that Dallio, mechanic Jack Wilson and friend Stormy Mangham vowed there and then to build their own machine to wrest the record back.

So began a series of events that would culminate with the production Triumph Bonneville and change motorcycling forever.

Their first bike, called The Devil’s Arrow, was a streamliner with a Triumph Thunderbird 650 engine tuned by Wilson and tested at pilot Mangham’s airfield in Fort Worth in 1954. Local flat track racer Johnny Allen was the rider and the first Bonneville record attempt followed in August 1955 reaching 191mph although, set just one-way, it didn’t qualify as a new record.

Bill Johnson of US Triumph importers Johnson Motors then helped finance the project, recognising the potential publicity value and three weeks later they returned to Utah to post a two-way record-breaking average of 192.3mph… before it was ruled out on a technicality.

Both the NSU and Triumph teams returned in 1956. On August 4 the Germans set a new record of 211.40mph before heading home to display the bike at September’s prestigious Cologne Show. But they were premature – the Johnson Motors squad arrived on September 4 with a new white bike in now dubbed ‘The Texas Ceegar’. Two days later they posted an average of 214.40mph.

As it turned out, the FIM never ratified the record leading to a number of fruitless legal actions. But as far as the forthcoming Triumph Bonneville was concerned, however, it didn’t matter. Johnson Motors, Triumph and Dunlop set a publicity storm in motion and the streamliner was shipped to Britain for that year’s Earl’s Court Show.

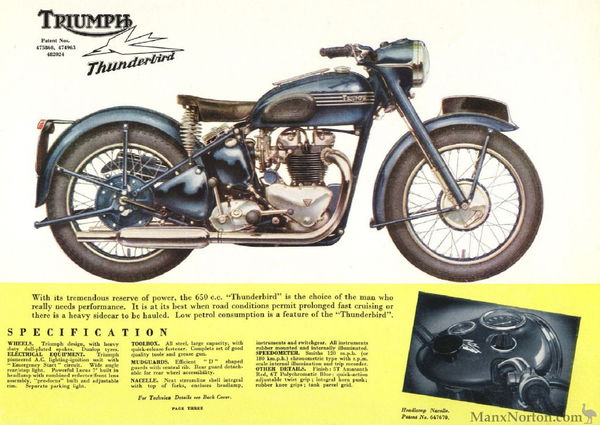

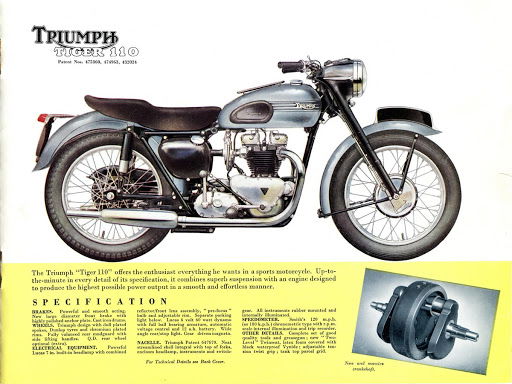

Yet the publicity also served to focus US attention on Triumph’s then range – not all of it favourable. In 1956, Triumph’s biggest bikes were its 650 Thunderbird tourer and single-carbed Tiger T110, both dwarfed by Harley’s already 1200cc FL HydraGlide. Americans wanted more, and with US sales vital, Meriden relented – albeit somewhat reluctantly.

Turner, although grateful for the land speed record publicity, was wary of high-performance road bikes so instead sought a relatively simple and swift solution. In 1957 Triumph was about to produce its first splayed head, twin-carbed version of its smaller, 500cc twin and also offered a splayed port, ‘Delta’ twin carb head as an option for the Tiger T110. But a production twin carb 650 wasn’t yet in the range. That would now change.

By March 1958 a twin carb 650 was on the test bench with the first complete prototype was running by August (which was when Turner, still unconvinced, made his infamous ‘Carey Street’ comment).

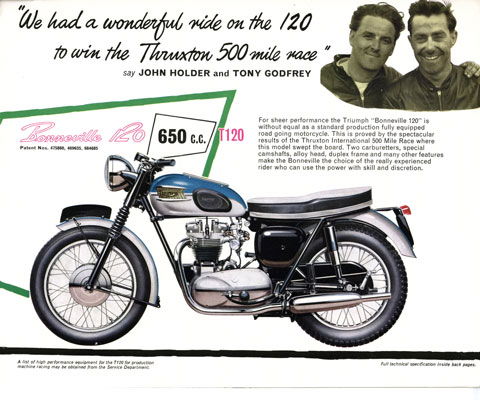

Triumph’s US distributors, however, were more enthusiastic and not only persuaded Turner to put the newcomer into production but to call it Bonneville to commemorate Allen’s achievements.

The resulting T120 Bonneville, (The ‘T120’, as with the T110 Tiger before it, indicating claimed top speed) was unveiled at Earl’s Court in November 1958 where it was the star of the show.

In truth, however, the Bonneville’s sales success was far from certain. Early bikes at a small press launch in September proved unreliable, forcing delays. (In truth the T120 was much more than just ‘a T110 with twin carbs’ – it also had high lift cams, bigger valves, higher compression and more resulting in a class-leading 46bhp but also causing one of the test bikes to drop a valve, leading to a redesign with stronger springs.)

Those delays meant the new Bonneville wasn’t even included in Triumph’s 1959 model catalogue while a UK recession and rushed styling decisions (the first Bonnie shared the Tiger’s heavily valanced mudguards and headlamp nacelle, neither of which appealed in America which preferred a ‘stripped-down’ hot rod look, both hit early sales.

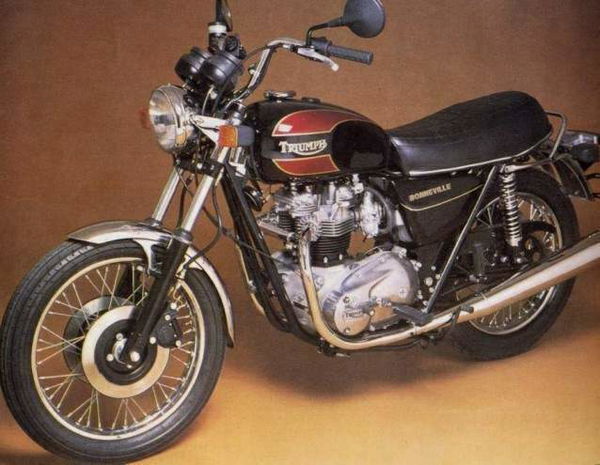

Ultimately, however, those blips didn’t matter and although a ‘slow burner’ in terms of sales the 650 Bonneville evolved throughout the 1960s to become the most desirable British bike of all. A new duplex frame came in 1960, unit construction arrived in 1963 and by 1967, when 28,000 examples were sold in the US alone and the Bonneville also won the Production TT, it was the most successful Triumph ever. 1967 was also the year on which the revived Hinckley Bonnevilles were modelled.

And although later 1970s 750cc versions, now outpaced by the latest Japanese superbikes, may have sullied the memory of the sublime ‘60s 650s, while the collapse of the British bike industry overshadows its earlier world dominance, the original Meriden Bonneville overall remains a true British motorcycling legend. Between 1959 and 1983, 385,000 were sold. No wonder modern Hinckley Triumph keeps building new ones today.